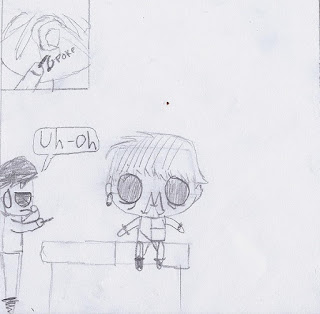

My son is also an artist, and his drawing are really coming along. To commemorate the occasion of the 'piercing', he drew a comic. I leave it here in its unedited form for your enjoyment. Then, I shall deconstruct.

I produce it again, with my commentary.

Please note the startlingly accurate drawing of the fine 2000 Volvo V7O I drive. He's got it right; down to the always-flat tire in the front. And, I did only allow for 20 minutes. It's only a little ear, after all (also, I only had 35 cents in my pocket).

Let me brag about the reversal of the "Two Trolls Tattoo Den" sign as seen from the inside. That's Paul sitting down trying to look like he wants to be there. That's me paying, 'tho it must be said I did not actually hand over the cash until I was sure the deed was done.

The child does get his spelling skills from his mother, but he was under duress at the time. Also note that we have definitive proof in the speech bubble that adults DO LIE TO CHILDREN. This is not, as some believe, an attempt to make it easier for the kid. Its intent is to make it easier on the adult. Paul is sitting down here, so as not to faint. I am not in the room.

The close-up of the ear is an actual technical drawing from THE ART OF THE PIERCE, p. 26 (1863). The 'uh-oh' is a direct quote, and the moment when the piercist realised he could have been a taxi driver. Those careful readers out there will have seen the increasing 'unhappy' on the child's face, and the fact that the father has completely disappeared from the frame. That's 'cause he was on the floor.

This last frame is complete fabrication. It was I doing the crying, not the child. It's interesting to note that insurance companies do not pay for damage done by flooding when the culprits walked into the situation at their own request. To reward our collective bravery, all involved went to Tim Hortons for a doughnut.

There you have it, folks. I do hope you've enjoyed this Christmas installment of "Things I Never Thought I'd Let Anyone Do To My Kid". Next year, God forbid, we'll be perusing those tattoo books lying on the table in the waiting room.